Samantha Lee/Insider

Latinos descend from more than 20 different countries, speak different languages, hold different political affiliations, and are of different races.

Yet they are categorized by the same few terms.

This group of people is complex and nuanced, but like many other ethnic and cultural demographics, it is often flattened into one mold.

"All Latinas don't look like JLo," Angel Jones, an Afro-Latina assistant professor of education at Southern Illinois University – Edwardsville, said.

"Afro-Latinos and indigenous Latinos are left out of the celebration. We are not seen. We are not heard. Our identities are not valued or even considered and that absolutely needs to change."

Hispanic Heritage Month is designated as an all-encompassing celebration of Latinos and their cultures. Yet, many say it falls short of that endeavor. Instead of celebrating Latino cultures, it commodifies them, all the while promulgating a one-dimensional portrait of who Latinos are.

This "fetishization" of Latinos during such a narrow period is why some are calling for the month to be reimagined.

"I'm proud and grateful for any opportunity I get to share the stories of our people, to highlight the beauty that is our community," Jones told Insider.

"But it's as if we don't exist September 14 and as if we cease to exist October 16."

President Lyndon B. Johnson signed a bill establishing Hispanic Heritage Week in 1968. Twenty years after President Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon expanded the acknowledgment a month that would cover several Latin American countries' independence days, including Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and Chile.

In acknowledging that Latinos are a culturally diverse, vibrant, and growing community, Voices of Color presents 'Mi Gente' - a series that speaks to the intricacies of having Latin American roots.

From personal essays about reclaiming Spanish language, exploring how the Puerto Rican diaspora's views towards the island's political status, to the role Hispanic-owned banks serve in making finances more accessible in underserved communities, among others, you'll find that Latino identity is far from one-dimensional.

With labels like Hispanic, Latino, and Latinx, come joy, pride, pain, and historical baggage. It's only by leaning into and committing to these complexities, that Hispanic Heritage Month can be the impactful period of visibility it's designed to be, experts say.

So who are the Latinos living in the US?

From country-of-origin to Spanish skills, Latino identity is complex

Mexicans compose the biggest share of the Latino population, with more than 60% of Census respondents identifying as members of this ethnic group. But the number of Latinos listing El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala as their families' countries of origin has grown in recent years as migration patterns shifted.

Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, Cubans, Colombians, Ecuadorians, and Peruvians are also among the top 10 groups with Latin American roots in the US.

As Hispanic Heritage Month is underway, Latino communities are continuously evolving, staking a greater claim in politics, Hollywood, and other industries and re-conceptualizing the way they identify.

According to Census data, 26.7 million Hispanics identified as white in 2010 compared to 12.6 million in 2020.

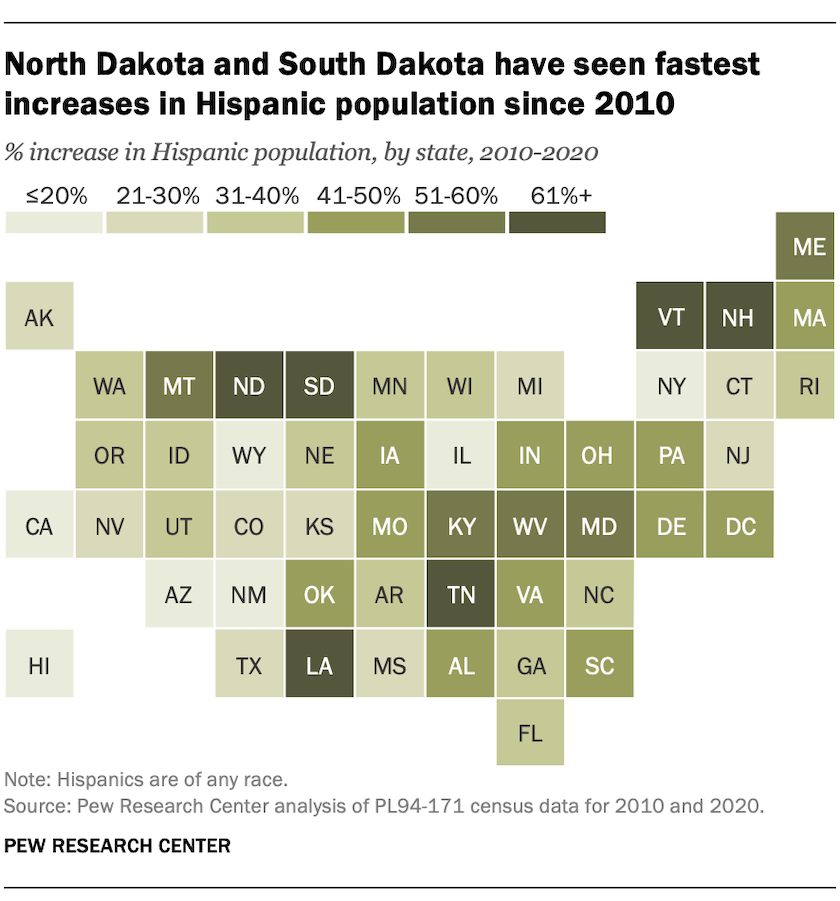

Hispanics are now the largest ethnic and racial group in California and three states - Florida, Texas, and California - saw their Latino populations grow by more than one million in the last 10 years. Perhaps more notable, North Dakota and South Dakota have seen the fastest Latino population growth since 2010, according to the Pew Research Center.

Because these communities are so vast, celebrating their nuances during Hispanic Heritage Month becomes difficult, said Ed Morales, author of the book "Latinx: The New Force in Politics and Culture."

"Outside of people who are involved with Latino advocacy and education and political organizations, the month itself does not seem to be observed by individual Latinos," Morales said. "It's more likely that Latinos celebrate holidays and traditions that are specific to their culture."

He cited the Puerto Rican Day parade, an annual event that takes place in New York City, as one Puerto Ricans are more likely to celebrate than Hispanic Heritage Month.

The name Hispanic Heritage Month itself might be deterring some people from acknowledging it, he added.

The longstanding debate about whether to label people with Latin American roots as Latino, Hispanic, Latinx, Latine, or by the country their family is descended from has erupted in recent years.

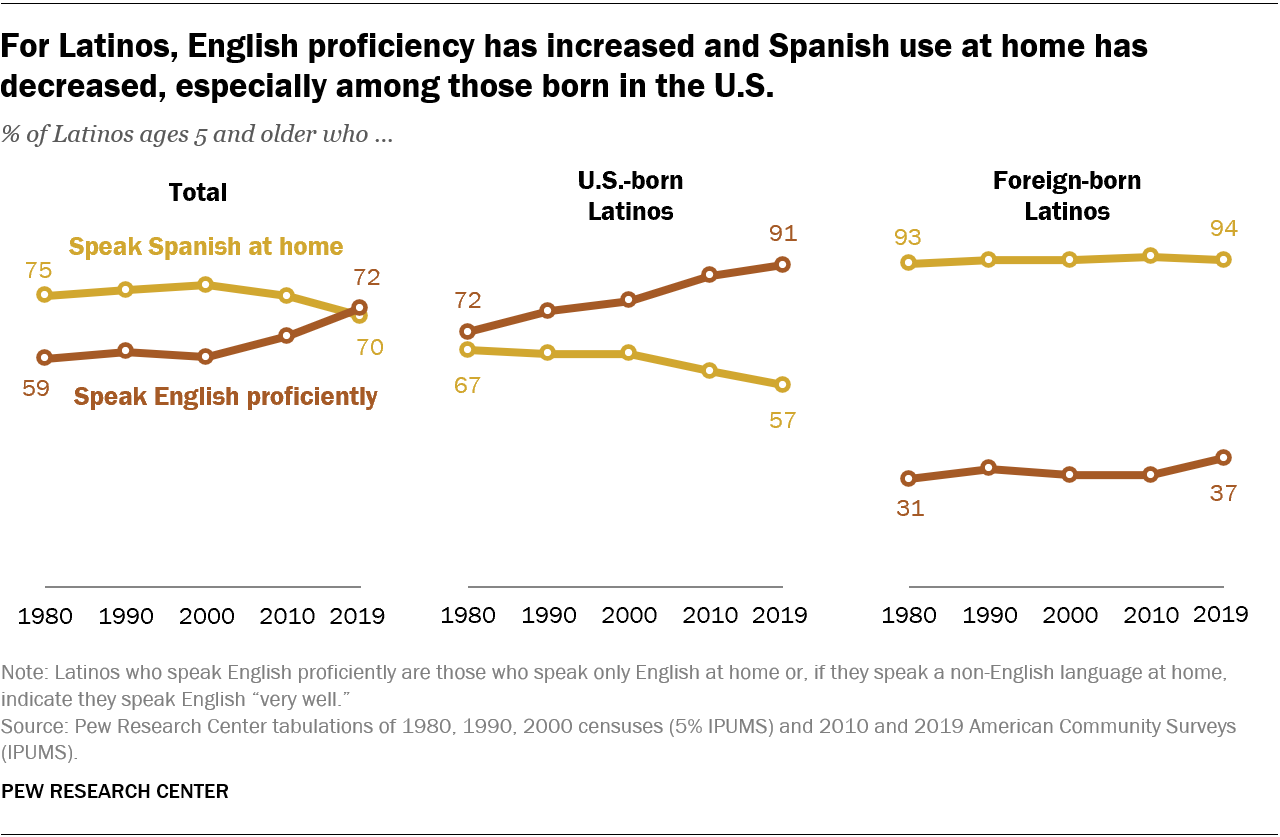

Given that nearly 15 million Latinos recorded only speaking English, per 2019 American Community Survey data, some argue that Hispanic does not feel like the appropriate moniker. Others don't like the label because they think it elevates their cultures' colonization as Spain colonized most of Latin America.

In the early 1900s, the US government labeled all Spanish-speaking people and those with Latin American roots as Mexican, even if their family did not descend from Mexico, per the Pew Research Center.

On the 1970 Census, Latino identity was expanded to include Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central or South American, and "other Spanish." Ten years later, Hispanic became part of the public lexicon when the category was used on the 1980 Census.

The categorization came about in large part because Mexican-American activists lobbied the Census Bureau to change the way Latinos were counted. While the label marked progress in helping Latinos gain political clout, some say it contributes to their erasure.

"Growing up, I despised being labeled Hispanic," wrote journalist Araceli Cruz in an essay for Teen Vogue. "It made me feel as if my Mexican and indigenous side was being wiped out."

Yet the term Latinx doesn't make everyone happy either. While many argue it's inclusive of people who do not adhere to the gender binary, others say the term is elitist.

Can moving on from 'Hispanic' make a difference?

Some haven't even heard of it. Per the Pew Research Center, more than 75% of Latino adults have not heard the term Latinx and of those adults who have, only 3% use it themselves.

Given that people with cultural connections to Latin America hold divergent thoughts about how to identify themselves, would changing the name of Hispanic Heritage Month be productive?

Laura Gómez, author of the book "Inventing Latinos: A New Story of American Racism" and a professor of law at University of California, Los Angeles, said she thinks so.

Changing the name from Hispanic Heritage Month to Latino History Month, in her view, would help crystallize what the month is about: honoring Latinos and drawing attention to the historical and cultural narratives about Latino communities that have often been effaced.

"Not only would it be consistent with Black History Month, but heritage means a lot of different things to different people," Gómez said. "We do have a common Latino history that we can talk about and look at, given our various countries have been colonized."

"Colonialism and US imperialism are much more concrete than heritage," she added.

It's as if we don't exist September 14 and as if we cease to exist October 16.Angel Jones, Southern Illinois University - Edwardsville

But whether changing the name of the month would be more "symbolic" than revolutionary remains a question, particularly if there's no meaningful commitment to elevating those who've traditionally been omitted from the celebration.

"For schools and corporations celebrating, this is not a time to perpetuate stereotypes about Latinidad," Jones said, mentioning the commodification of Cinco De Mayo as a poor example of engaging with Latino culture.

"I think they really need to be mindful about what it is they're doing and why they're doing it."

Re-envisioning a more inclusive celebration

Just as the Hispanic Heritage Month can serve as a way to highlight Latinos, it can also be rife with half-baked attempts at inclusion, said Jones cautioned.

Hispandering - which refers to trying to convince Latino voters or consumers for buy-in with often ineffective and offensive marketing - also takes place during this month.

"While Latinos should be consulted in this kind of educational work, they must be effectively compensated for their intellectual and emotional labor," Jones said.

Though Hispanic Heritage Month is imperfect, many say the holiday still serves an important purpose not only in allowing Latinos to appreciate their culture amid the pressure to assimilate, but by increasing visibility of Latino communities.

"When I was growing up in Albuquerque in the 1970s, I never learned anything about Mexicans or Latinos," Gómez said. "I ask my students if they have learned this history and only a few of them have … There's a real need to right the wrongs of this exclusion."

That's why Gómez is a proponent of educational initiatives throughout the month that attempt to fill the gap in inferior historical education about Latinos and other minoritized groups.

As the month is underway, Voices of Color will continue to spotlight Latino communities and all their invaluable contributions with narratives celebrating the agency of people to define themselves, tell their own stories and shape their own future.